As noted in a recent gallery marking the 175th anniversary of Anti-Slavery International, photographs and images have long been central to antislavery campaigns. In this guest post drawn from a longer article, historian Zoe Trodd asks what contemporary anti-slavery activists can learn from past uses of imagery and highlights pitfalls future activists should avoid.

Over the past 15 years, the antislavery movement’s visual culture has depicted a world of 30 million slaves. Beyond the inevitable presence of chains and bars, much of this visual culture uses four main tropes: the supplicant slave, the scourged back, the auction block and the slave ship. All four have antecedents in influential eighteenth- and nineteenth-century icons. Yet by using earlier imagery as a model, contemporary activists often repeat the mistakes of their forbears. They reinforce the paternalism and sensationalism that marked some of the first abolitionist movement’s visual culture. With some exceptions, today’s antislavery visual culture heroizes the abolitionist liberator, minimizes slave agency and pornifies violence.

The Supplicant Slave

The most common theme in contemporary imagery dates to October 1787. Designed by Josiah Wedgwood’s pottery firm, the British abolitionist seal featured the slogan “am I not a man and a brother?” A kneeling figure with pleading hands asks humbly for compassion, poses no threat through rebellion or resistance, and would gratefully receive freedom. The image invites not solidarity with the enslaved but paternalistic association with the morally righteous abolitionists who will answer the captive’s question by releasing his chains.

Today, the supplicant slave has a second life, pasted in its original form onto flyers and websites for events and campaigns. Enhancing the visual rhetoric of humility, Ken King issued an antislavery medallion in 2010. It featured a woman in contemporary dress with the message: “Am I Not a Daughter and a Sister?” This slave can’t even reach out hands in supplication, instead buries her head despairingly in her knees. King confirmed the enhanced emphasis on helplessness by adding the words: “Speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves” (Proverbs 31). As well as these explicit reuses of the original design, supplicant hands are raised again across contemporary imagery: clasped together, bound at the wrist by chains, rope, airline luggage labels, barcodes or price tags, lifted to rest against walls, windows or bars, with messages (“help me” or “stop slavery”) on outstretched palms, all underscoring a message of passivity and gratitude.

The Scourged Back

The second most common trope in contemporary antislavery visual culture is the scourged back. It draws most obviously from a nineteenth-century photograph of a slave identified as Gordon whose back was scarred by whippings. Abolitionists circulated copies and Harper’s Weekly published a woodcut version on July 4, 1863. It was the latest in a long line of antislavery images that depicted violence against the slave body and risked dehumanization within what Karen Halttunen terms an abolitionist “pornography of pain.” Slaves are flogged, sometimes naked, sometimes hanging from trees, and often surrounded by observers who gaze at their exposed bodies. Slavery’s ritual violence is inscribed on the body, a story for all to read and understand.

The whipped back is exposed again today as a symbol of slavery’s brutality and a stand-in for an enslaved person’s whole experience. Photographs published by newspapers or NGOs show backs scarred by melted plastic or whips. One artist has even managed to combine two tropes. In 2012, the photographer Steven James Collins exhibited a series of color photographs titled Modern Day Slavery. In one, a black man with vacant eyes and a naked chest raises shackled hands in an “Am I Not a Man” gesture. In another, the same model reveals a back covered in bleeding scars. And in a third, the scourged back is on display while the man kneels in shackles, one arm outstretched pleadingly—here asking “Am I Not a Man?” and revealing the Scourged Back. This imagery has also extended to several manipulated photographs of women with words or barcodes on their backs, the scars of the original photograph updated as messages or coded lines that brand individuals as property and tell slavery’s story.

The Auction Block

A third major trope is the auction block, which featured in the Liberator masthead from 1831 to 1865 as a scene with crowds of onlookers. The famous masthead responded to what Saidiya Hartman terms slavery’s “obscene theatricality.” If a slave society has to demonstrate enslavement, relying on the power of spectacle to create its prevailing order, as Joe Lockard has argued, then the auction block was a demonstration of the slave’s chattel status—a spectacle of submission. Abolitionists repeated the spectacle. After the first appearance of the Liberator masthead, they published numerous tableau illustrations of slave auctions, many of which could be mistaken for theatrical performances.

The antislavery auction is back. In 2012 the Salvation Army put children in boutique windows in a Johannesburg shopping mall. They stood behind glass with a banner behind them that read: “Sale. 3-6 year olds. 7-10 year olds. 11-14 year olds.” The same year, the Task Force on Human Trafficking opened an installation called “Woman to Go,” featuring real women sitting or standing on blocks behind glass in a shopping center in Tel Aviv, each with a price tag and barcode. These updated auction scenes put slaves on display, reaching for shock value but risking sensationalism and objectification. We are onlookers at a spectacle where the slave is center-stage but powerless.

The Slave Ship

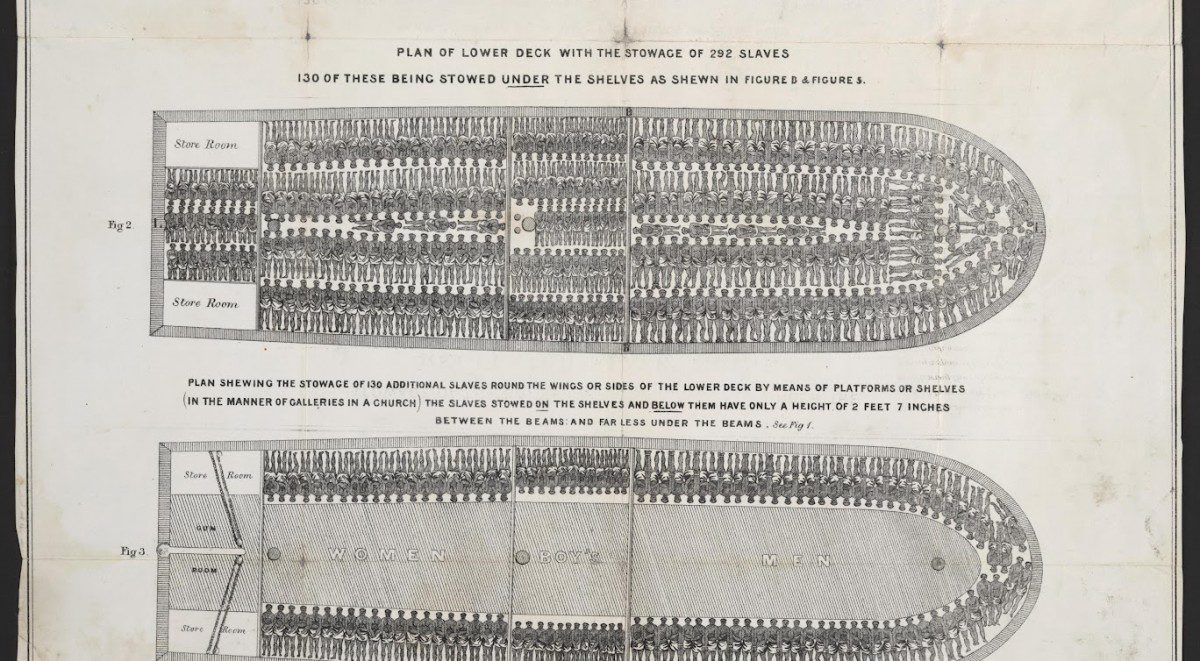

The last major trope is the slave ship. Here campaigners borrow from the widely-distributed Brookes diagram, designed by British abolitionists in 1788, which used rows of tiny black figures to show the cramped conditions of the Middle Passage. The diagram reinforced notions of black passivity with its supine figures and denied individuation with its lack of any distinguishing features for the slaves.

Seemingly unaware of the diagram’s reductive qualities, contemporary abolitionists revisit it. They publish cutaway diagrams of trucks, speed boats, or plane cargo holds, with the same rows of tiny black figures. They also circulate a host of Brookes allusions—edited photographs of women tightly packed against one another in Styrofoam or bottled on store shelves, tiny hunched figures squeezed into neat rows. And at least one image has brought together all four tropes while still emphasizing the process of a new Middle Passage that packages people for sale. In 2009, the Luxembourg Government’s anti-trafficking campaign included a photograph of a naked woman squeezed under a tight plastic wrap (slave ship), marked by a barcode as a slave (scourged back), arms raised pleadingly (supplicant slave), and placed on the glass counter of a supermarket (auction block).

Visual Futures

There have been a few exceptions to all this. In contrast to the supplicant slave imagery, Anti-Slavery International’s logo uses a raised arm that is closer to a power fist than a pleading hand, lifted upward against a blood red background and clenched around a large key. This slave firmly grasps his or her own freedom and raises an arm in victory rather than supplication. More than 200 years after Wedgwood’s slave knelt down, someone finally imagined him standing up.

In contrast to the trope that brands individuals’ experiences onto their backs, the No Project released a poster in 2012 titled “Wearing Her Story,” made by the artist Ismini Black. A woman’s dress hangs alongside carcasses in a butcher’s window. There are letters cut out of the dress and the words are impossible to piece together. By replacing a woman’s body with just her dress, the poster refuses to inscribe slavery’s story onto her flesh. She might wear her story like a removable item of clothing, but it is not the last word on her total identity. Instead it remains impossible to grasp and therefore consume, unlike the poster’s chunks of meat. More than 150 years after Gordon exposed his back, someone finally refused to display the scars.

In contrast to the auction block imagery, MTV EXIT opened an exhibition in Hanoi in 2012 that included an installation by Doan Hoang Kiensaid. Crystal bottles contained pieces of hair from 120 different people. Each bottle was labelled with codes for sale. The installation refused the idea that a human being can ever be wholly traded or owned, offering for sale only a small, replaceable part. Nearly 200 years after the Liberator masthead’s slave mother stepped onto the auction block, someone finally acknowledged that she could not be bought.

Romuald Hazoume’s installation La Bouche du Roi (1999) is an exception to the fourth category. It has 304 masks made from plastic petrol cans laid out in the shape of the Brookes, each can representing a person, and includes film footage of people enslaved in the industry that smuggles petrol between Nigeria and Benin. Hazoume restored individuality by also including the sounds of people speaking in the indigenous languages of Benin, and items related to the customs of the Yoruba people. More than 200 years after the Brookes first opened its top-deck to reveal the figures packed inside, someone had seen their faces.

So a few artists have applied history’s lessons and reached for a liberatory aesthetic. Moving forward, the antislavery movement might take its lead from Black, Kiensaid and Hazoume. It should work to replace nostalgia with protest memory—memory of protest used to protest—and salvage from the antislavery past a visual culture of slave rebellion and black activism, rather than slave passivity and white paternalism. Seeking a less abusive usable past, and learning lessons from the first antislavery movement’s failures, successes, contradictions and unfinished work, it should forever forego the kneeling slave of the “Am I Not a Man” medallion. He is a figure who stood tall long before Emancipation, who answered his own question again in 1968 with “I Am a Man” civil rights banners, and who wonders disbelievingly of much contemporary imagery: am I still not a man?

Zoe Trodd is Professor of American and Canadian Studies, University of Nottingham. For more on the ideas explored in this post, see her article “Am I Still Not a Man and a Brother? Protest Memory in Contemporary Antislavery Visual Culture,” in Slavery & Abolition (2013), available online.

5 Comments, RSS