By Robert E. Wright, Nef Family Chair of Political Economy and Historians Against Slavery Treasurer

With my history of Financial Exclusion in America hot off the presses, I recently turned my attention to global financial crises only to bump, once again, into pauper auctions, a theoretically interesting type of bound labor barely mentioned in Poverty of Slavery, my 2017 global history of the negative externalities created by the enslavement of sentient beings.

In Anglo-America and other parts of the European world in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, cash-strapped local governments auctioned off paupers to the lowest bidder, the business willing to put the impoverished individual to work for the lowest government subsidy payment. Auctions occurred when, in the absence of subsidy payments, businesses could not afford to pay paupers a subsistence wage for their labor, in cash or in kind, because the poor were not productive enough and/or general economic conditions did not merit it. Under the auction system, local governments and employers essentially shared the expense of each pauperized worker’s subsistence.

When it functioned properly, the auction system ensured that local government paid as little as possible to support the poor, freeing up resources for other uses. It was easier to administer than running a public workhouse and presumably encouraged more productive endeavors. Even if the work was not wholly merited by economic conditions, pauper auctions put the poor to work, which most Americans believed was a good thing in and of itself because labor encouraged good habits, built skills, and stymied vice.

The main problem with the pauper auction system was that it turned impoverished persons, mostly women and children, into cheap, temporary slaves who were more akin to modern slaves, to the disposable people described by Kevin Bales, than to the antebellum South’s iconic chattel slaves. Unsurprisingly, New York’s Yates Report (1824) claimed that auctioned paupers were “frequently treated with barbarity and neglect by their keepers.” Other successful keepers, though, were faulted for going too easy on their poor charges, which in the parlance of the time could lead only to their idleness and dissipation.

Like other types of unfree laborers, the poor who were “farmed out” to the lowest bidders resisted their bondage as best they could by shirking and absconding. What condemned pauper auctions in America was not concern for the poor, or the state of the overall economy, but abuse of the system by people who conspired to bid on friends and relatives in order to acquire the subsidies. Poorhouses came to be preferred because, unlike the uneven auction system, the uniformly poor condition of poorhouses minimized costs by attracting and retaining only the most desperate individuals. Pauper auctions continued, however, in parts of Canada and Europe into the 1880s and 1890s.

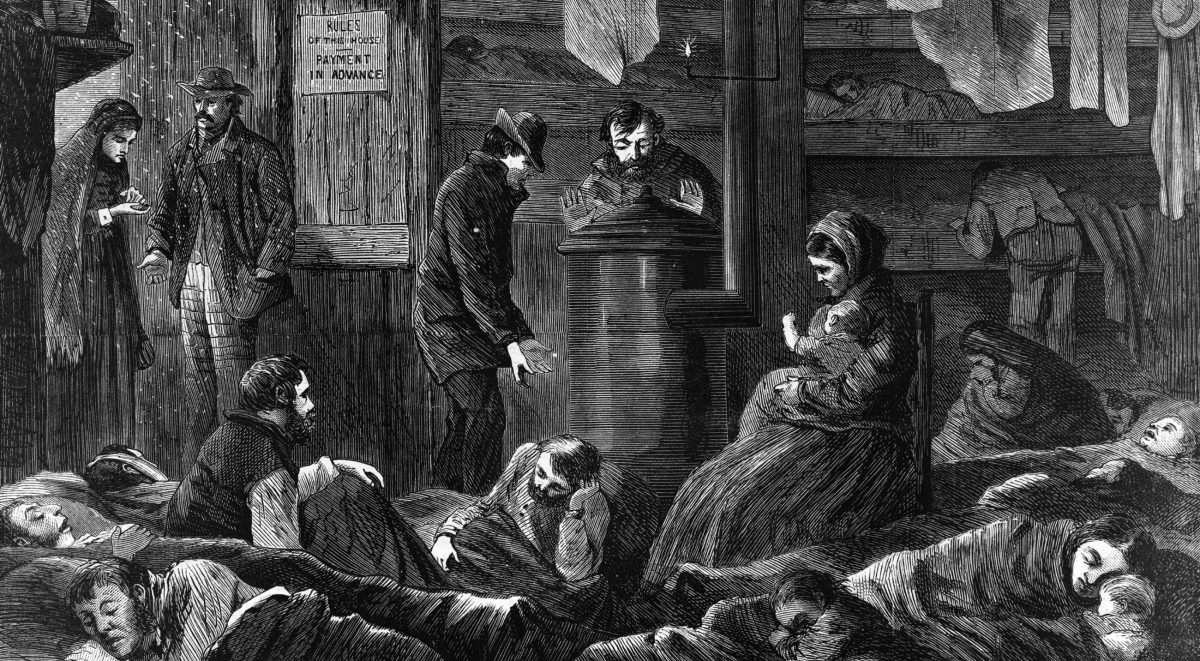

In some places, local governments merely outsourced the entire workhouse or almshouse to the lowest bidder, which sometimes led to conditions similar to those found in various notorious convict labor systems. Many contractors found it in their best interest to exploit pauper bodies, through overwork and under nourishment, until they moved no more. Homo homini lupus, as Freud once wrote.

Those interested in learning more about pauper auctions in the U.S. might start with Benjamin Klebaner’s classic article, “Pauper Auctions: The ‘New England Method’ of Public Poor Relief,” Essex Institute Historical Collections 9, 1 (1955): 195-210, followed by Robert E. Cray’s Paupers and Poor Relief in New York and Its Rural Environs, 1700-1830 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988), and Michael B. Katz, “Poorhouses and the Origins of the Public Old Age Home,” The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 62, 1 (Winter 1984): 110-40. For Canada, England, and New England, try James M. Whalen, “Social Welfare in New Brunswick, 1784-1900,” Acadiensis 2, 1 (Autumn 1972): 54-64. For a view from Scandinavia that highlights the harsh conditions often imposed on children by the auction system, see Marjatta Rahikainen, “Compulsory Child Labour: Parish Paupers as Indentured Servants in Finland, c. 1810-1920,” Rural History 13, 2 (October 2002): 163-78.