The Lepers in Our Heads

Chris Momany, Adrian College

Have you come here for forgiveness?

Have you come to raise the dead?

Have you come here to play Jesus

To the Lepers in your head?

Bono/U2

It is a good thing that many of our most prestigious colleges and universities are finally coming clean about their entanglements with Atlantic slavery and its lingering effects. Symposia, exhibits, publications, artistic interpretations, and other forms of looking in the mirror matter. Yet I must confess a reservation.

There is a fine line between necessary truth and reconciliation and self-congratulatory repentance. The scales can be tipped toward the latter when an institution already possesses a particularly generous opinion of itself. The most searching confrontation with our past might be pitched as an academic virtue – even a badge of urbane prowess. The academy is a beautiful place, but its culture of intellectual caste, advancement, and one-upmanship sometimes leads to rather strange implications, if not outright self-righteousness. The process of exercising demons might only serve to help respectable institutions feel better about themselves. I’m reminded of the lyrics to a U2 song: “Have you come here for forgiveness? Have you come to raise the dead? Have you come here to play Jesus to the lepers in your head?”

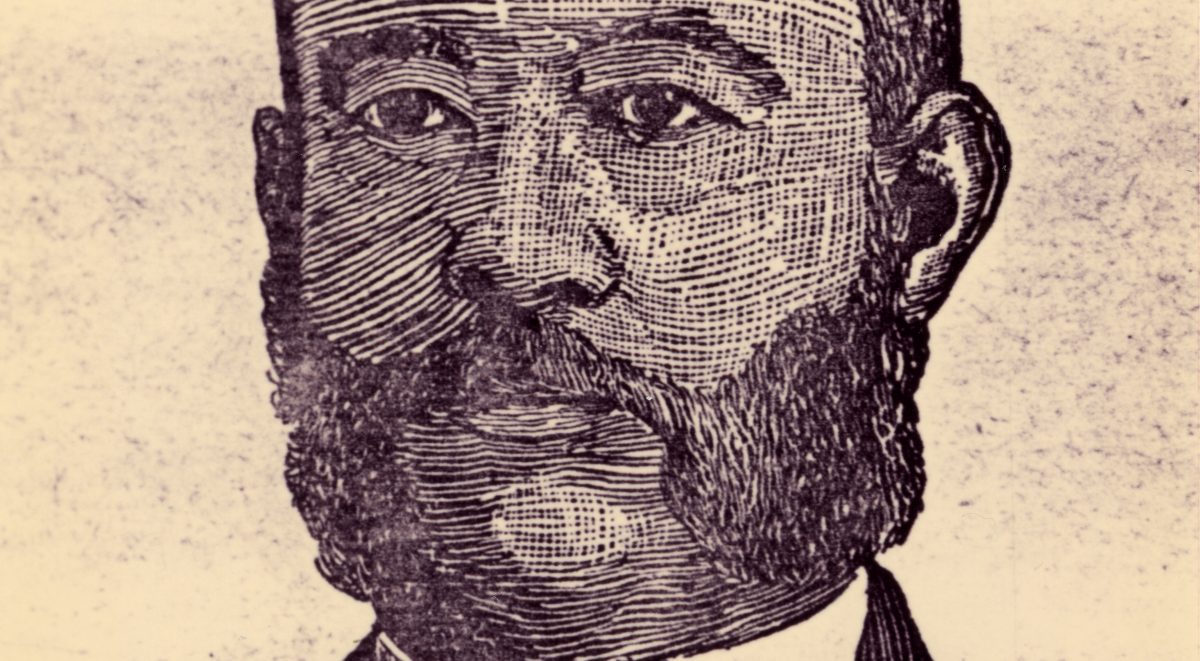

This phenomenon among flagship universities is expressed in many forms. Perhaps a common characteristic is the way such institutions insist on maintaining control over the conversation. I experienced one version of the dynamic during the past two years while researching material for my book, For Each and All: The Moral Witness of Asa Mahan (Foundery Books, 2018). I teach and write from Adrian College in Michigan, a small liberal arts institution founded by veteran abolitionists in 1859. One of our first students was William Henry Butler (later known as Henry Fitzbutler). Fitzbutler was the son of formerly enslaved/indentured parents from Virginia. He grew up in what is now Ontario and crossed into the United States immediately before the Civil War, pursuing studies at our fledgling school. Those, of course, were the days when emerging studies in the sciences and medicine could be combined with literary rigor and examination of the “classics.” Fitzbutler did it all at Adrian College and even served as an officer of our primary Literary Society. Later, while a physician in Louisville, he edited a newspaper that became critical for the African American community. After several undergraduate years among Adrian College, Henry Fitzbutler breezed through the medical school program (less than one year) at an institution that now boasts an international reputation.

Those of us at inconspicuous Adrian College have enjoyed learning Dr. Fitzbutler’s story, and an abbreviated version of it appears in my book. However, the only known drawing of Fitzbutler is not from Adrian College. It is a sketch specifically created by an artist almost seventy years ago. Each time we have reproduced this image, we have consulted the nationally-revered archival collection at the same prestigious institution where Fitzbutler received his medical degree. They have been willing to grant permission for reproduction – at a price. We followed this procedure for several years. Then I decided to phone the archives at the University of Louisville, where some of Fitzbutler’s later legacy is memorialized. To their credit, the archival professionals in Louisville said they had no right to grant permission for use of the Fitzbutler drawing, but more importantly, they suggested that the previously mentioned “prestigious” institution in Michigan also did not possess the prerogative to serve as gatekeepers for the image.

Those of us at inconspicuous Adrian College have enjoyed learning Dr. Fitzbutler’s story, and an abbreviated version of it appears in my book. However, the only known drawing of Fitzbutler is not from Adrian College. It is a sketch specifically created by an artist almost seventy years ago. Each time we have reproduced this image, we have consulted the nationally-revered archival collection at the same prestigious institution where Fitzbutler received his medical degree. They have been willing to grant permission for reproduction – at a price. We followed this procedure for several years. Then I decided to phone the archives at the University of Louisville, where some of Fitzbutler’s later legacy is memorialized. To their credit, the archival professionals in Louisville said they had no right to grant permission for use of the Fitzbutler drawing, but more importantly, they suggested that the previously mentioned “prestigious” institution in Michigan also did not possess the prerogative to serve as gatekeepers for the image.

It turns out that the drawing of Henry Fitzbutler bears a more complex and more instructive narrative than many grasp. The sketch of Dr. Fitzbutler was originally featured on the cover of the Journal of the National Medical Association in September 1952. The artist, a woman named Naida Willette Page, deserves so much more credit for her work than she has received. The National Medical Association (located in Silver Spring, MD) is a jewel of scholarship and social conscience. According to the organization’s website:

“The National Medical Association (NMA) is the collective voice of African American physicians and the leading force for parity and justice in medicine and the elimination of disparities in health.” The NMA represents over fifty thousand physicians and the patients they serve. The NMA also possesses all rights to that artwork depicting Dr. William Henry Fitzbutler, and this was their reply to me when I asked permission for reproduction: “The NMA Publications Committee has granted permission for you to use the referenced image of Dr. Henry Fitzbutler in your book without charge.”

When we explore and interpret the story of slavery and its consequences, let’s not forget to note that academic appropriation of the narrative by today’s prestigious colleges and universities is part of the problem.

To the gracious professionals at the National Medical Association, I say: “Thank you so much for your rich history, generosity, and witness.” To the self-anointed guardians of academic excellence (and implied moral superiority), I say: “Please keep looking in the mirror.”

Christopher P. Momany is a chaplain and professor in the Philosophy/Religion Department of Adrian College. His forthcoming book explores the way moral philosophy was used to either justify or confront slavery during the antebellum period.

Christopher P. Momany is a chaplain and professor in the Philosophy/Religion Department of Adrian College. His forthcoming book explores the way moral philosophy was used to either justify or confront slavery during the antebellum period.