By Rachel Hooper

At Historians Against Slavery, we are assembling a list of colleges and universities with abolitionist ties in order to better understand the effect abolitionism had on colleges in the nineteenth century. This post reflects on my research with HAS and summarizes what I see as the five most important ways that abolitionism affected institutions of higher education.

1. Abolitionists demanded academic freedom.

Academic freedom is an important principle today in American universities, safeguarded by free speech policies and tenure. But the right for faculty to follow their conscience regardless of popular opinion was not always guaranteed by academia. The first inklings of the ideal of the free search for truth and its dissemination appeared in the mid-nineteenth century in debates over the nature of slavery and what could be done about it. Because anti-slavery arguments were countercultural and highly controversial, anti-slavery groups created their own educational institutions where their right to free debate would be protected. By the end of the nineteenth century, abolitionists who sought an immediate end to slavery had established over fifty colleges and universities from New York to Texas. As abolitionist students at Lane Seminary asserted in their petition to the school—“Proscription of free discussion is sacrilege!”

2. It started with fiery sermons.

Charles Grandison Finney preached that one could be free from sin here and now, and that it was the duty of Christians to rid themselves and their communities of sin, including the sin of slavery. Part of the Second Great Awakening in the 1820s, Finney was known for his passionate, evangelical sermons, which had profound emotional effects on his audiences. He was a millennialist, who believed that God was preparing the earth for Jesus to return and rule for a thousand years.

Slavery was an affront to this perfectionism because a master inevitably sinned in denying the moral agency of his slave. As Finney argued, “To enslave a man is to treat a person as a thing–to set aside moral agency; and to treat a moral agent as a mere piece of property.” Finney was recruited as a professor of theology at Oberlin College in 1835 and was appointed president of the college in 1851.

3. Students led the charge.

In 1834, Lane Seminary in Cincinnati hosted a series of debates on the topic—“Is it the duty of the people of slaveholding states to abolish slavery immediately?” After eighteen days of debates and roundtable discussions, the students, led by Finney’s former student Theodore Dwight Weld, concluded that slavery should be abolished immediately and Christians should not support the colonization movement, which advocated for the return of slaves to Africa. Their conclusions were so radical that they sparked pro-slavery riots, and the school’s administration attempted to stop the students’ activities. Fifty-one students withdrew from Lane and moved north to Oberlin publicly declaring that “free discussion, with correspondent effort, is a DUTY, and of course a RIGHT.”

4. Abolitionists chose strategic locations.

Abolitionist orator Wendell Phillips said in 1859, “God has set us this task: ‘If you want good institutions, do not try to bulwark out the ocean of popular thought, educate it.'” This idea aligns with an ethic of abolitionist evangelicals to colonize western states in the hopes of swaying public opinion against slavery. From their initial base of support in New York around Hamilton College and the Oneida Institute in Oneida County, anti-slavery academics began establishing communities and colleges in states within a few decades of their entering the union. For example, Maryville College in Tennessee (1819), Western Reserve in Ohio (1826), Illinois College (1829), Adrian College in Michigan (1845), and Beloit College in Wisconsin (1846). The University of Kansas and Washburn University (both 1865) were created by abolitionists who had earlier moved to Kansas to influence the vote on whether the state would accept or reject slavery.

5. Ideas came first, people later.

Abolitionist academics were activists, but they based their arguments against slavery primarily on logic and theology rather than compassion and a sense of common humanity. Only after the abolition of slavery seemed certain, did academics take a serious interest in those who suffered under slavery. George Whipple played a crucial role at this stage. Educated at the Oneida Institute, Lane Seminary, and Oberlin, Whipple was secretary of the non-denominational American Missionary Association, which worked with the Freedmen’s Bureau after the Civil War to establish universities in the south to educate freed blacks.

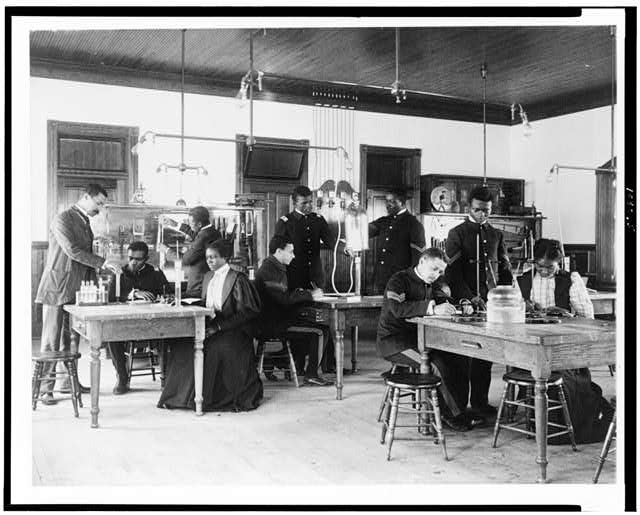

Women who had graduated from Oberlin and other abolitionist schools were recruited to teach in the South. Schools established by the AMA and Freedman’s Bureau such as the Hampton University (1861), Howard University (1866), Morehouse College (1867), and Fisk University (1867) educated the next generations of leaders in the fight for racial equality including Booker T. Washington, Thurgood Marshall, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Rachel Hooper is a doctoral candidate in Art History at Rice University.

Further Reading

- Dumond, Dwight Lowell. Antislavery: The Crusade for Freedom in America. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1961.

- Jeffrey, Julie Roy. The Great Silent Army of Abolitionism: Ordinary Women in the Antislavery Movement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

- Lovett, Bobby L. America’s Historically Black Colleges & Universities: A Narrative History from the Nineteenth Century Into the Twenty-First Century. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press, 2011.

- Maas, David E. Marching to the Drumbeat of Abolitionism: Wheaton College in the Civil War. Wheaton, IL: Wheaton College, 2010.

- McKivigan, John R., ed. Abolitionism and American Religion. New York: Routledge, 1999.

- Morris, Joseph Brent. “‘Be Not Conformed to This World’: Oberlin and the Fight to End Slavery, 1833-1863.” Ph.D diss, Cornell University, 2010.

- Muelder, Hermann Richard. Fighters for Freedom: The History of Anti-Slavery Activities of Men and Women Associated with Knox College. New York: Columbia University Press, 1959.

- Richardson, Joe M. Christian Reconstruction: The American Missionary Association and Southern Blacks, 1861-1890. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2009.

- Stewart, James Brewer. Abolitionist Politics and the Coming of the Civil War. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2008.

- Woodson, Carter Godwin. The Education of the Negro prior to 1861. Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, 1919.

Image credit: Class in capillary physics at Hampton Institute, Hampton, Virginia, Library of Congress

4 Comments, RSS