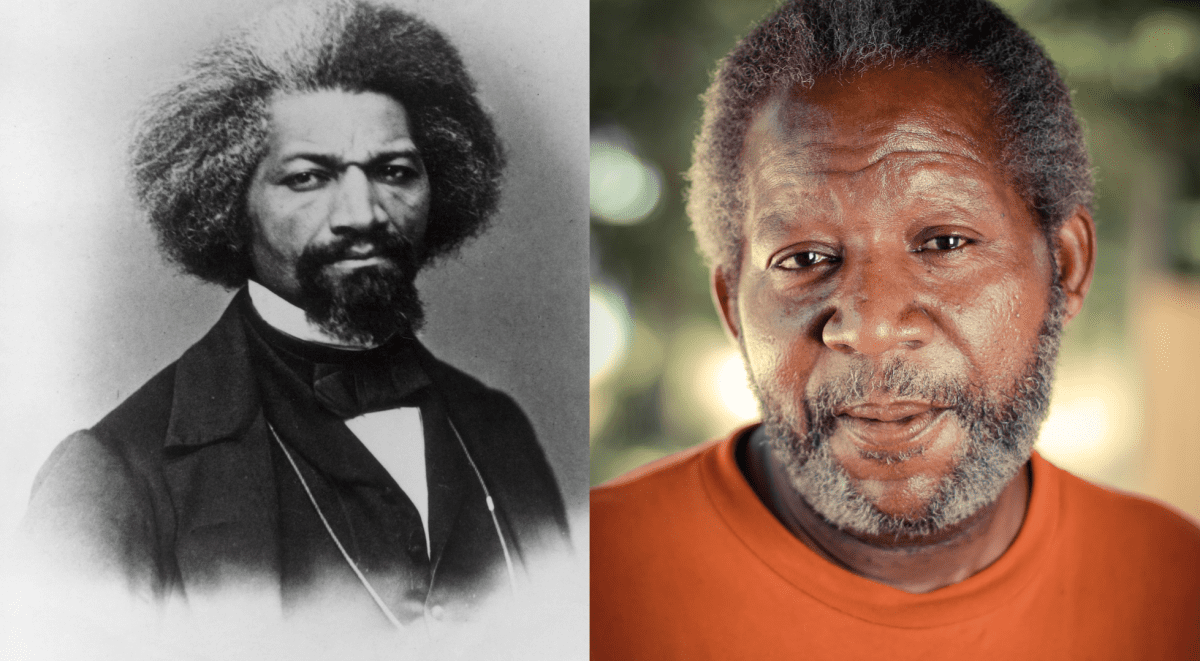

The role of exonerees from death row, like Clarence Brandley, in contemporary anti-death penalty efforts mirrors the role that former and fugitive slaves, like Frederick Douglass, played in efforts to abolish slavery.

By Bharat Malkani, Cardiff University

It has long been recognized that the criminal justice system in America is a vestige of racial slavery. All things being equal, a person is far more likely to face a death sentence and execution if they are accused of killing a white person, rather than a black person, echoing the belief in the antebellum era that the lives of white people are more important than the lives of black people. But while the legacy of slavery on the death penalty has received attention, the legacy of the abolitionists on the contemporary anti-death penalty movement has not. In Slavery and the Death Penalty: A Study in Abolition, I explore the historical and conceptual links between the respective abolitionist movements, and set out some lessons that today’s abolitionists might learn from history.

Radical versus moderate abolitionism

Historians disagree on how to characterize the disparate aims, motivations, and strategies of those who opposed slavery, but we can broadly categorize some as ‘radical’, and others as ‘moderate’. Radicals considered slavery to be a symptom of a deeper illness that plagued America, and situated their opposition to bondage within wider concerns with the constitutional and cultural order. Moderates, on the other hand, tended to focus solely on slavery, fearing that over-reaching would weaken the prospects of abolition.

This analytical framework helps shed light on the nature of anti-death penalty efforts today. At first glance, many features of contemporary death penalty abolitionism appear to be distinctly ‘moderate’. For example, the risk of executing an innocent person is a powerful abolitionist trope, but is an issue that is peculiar to capital punishment. Efforts to prevent departments of corrections from obtaining the drugs needed for lethal injections are similarly peculiar to capital punishment, and say nothing about wider issues with penal law and policy in America, such as solitary confinement, mass incarceration, and other harsh punishments. And in recent years, some abolitionists have been willing to offer life in prison without the possibility of parole as an alternative to capital punishment, hoping that death penalty supporters will forego executions if they are assured that the person in question will be permanently removed from society. This latter tactic is comparable to colonization. Founded in 1816, the non-radical American Colonization Society proposed the removal of free blacks to territories outside America, in the hope that supporters of slavery would accept emancipation if they did not have to countenance racial integration or equality.

Some in the anti-death penalty community have espoused the benefits of moderate, or pragmatic, approaches to abolition, pointing to declining support for, and use of, capital punishment. However, many slavery abolitionists knew all too well that there are downsides to this approach, and their warnings should be heeded today. David Walker provided a searing and prescient critique of anti-slavery activists who supported colonization, decrying them for normalizing and legitimizing the view that blacks were not equal to whites. Recently, historian Nicholas Guyatt has suggested that discourses of colonization entrenched racist ideas that have survived to this day, giving credence to Walker’s concerns. Just as radical abolitionists recognized that colonization should be rejected because it was premised on the same values that underpinned slavery, so today’s abolitionists should reject life without parole because it is premised on the same values that underpin capital punishment: that some people can and should be permanently removed from wider society.

In some respects, the benefits of a radical approach to abolition can actually be found in other aspects of anti-death penalty efforts. People with experience of capital punishment have become increasingly effective abolitionists, and the anti-death penalty movement should draw on the role that those with experience of slavery played in anti-slavery efforts. Historians have recognized that it was black abolitionists—those with direct experience of racial injustices—that imbued the anti-slavery movement with a radical spirit, since they were the ones who appreciated that abolition must encompass racial equality as well as mere physical freedom from bondage. Members of the organization Witness to Innocence, which comprises exonerees from death row and gives them a voice in the anti-death penalty movement, have the potential to mirror the radical role that former and fugitive slaves played in abolition, by delivering their personal narratives and drawing attention to the cultural and institutional factors that lead to wrongful convictions in the first place. In 1845, James Henry Hammond wrote to James C Calhoun that “A Slave holder… or Southern man who falters, who apologizes, much less who denounces Slavery & regards abolition as inevitable is in my opinion our very worst enemy, the man who saps our strength at the core & does more to destroy us than a brigade of abolitionists could.” Drawing on this observation, we can see the vital role that Public Safety Officials on the Death Penalty might play. Formed in 2016, PSODP consists of current and former law enforcement personnel, prosecutors, and corrections officials who have concerns with capital punishment. Like former slaveholders, they can sap the strength of the pro-death penalty lobby in ways that brigades of other abolitionists cannot. Even the efforts to stem the supply of lethal injection drugs echoes the radicalism of the abolitionists who refused to be complicit in slavery. William Lloyd Garrison was particularly notorious for challenging Northerners to speak out against bondage, and to refuse to co-operate with the institution of slavery. The refusal of pharmaceutical companies and foreign governments to help with the administration of the death penalty has every bit of abolitionist potential as the refusal in the antebellum era to assist with the return of fugitive slaves.

In some respects, the benefits of a radical approach to abolition can actually be found in other aspects of anti-death penalty efforts. People with experience of capital punishment have become increasingly effective abolitionists, and the anti-death penalty movement should draw on the role that those with experience of slavery played in anti-slavery efforts. Historians have recognized that it was black abolitionists—those with direct experience of racial injustices—that imbued the anti-slavery movement with a radical spirit, since they were the ones who appreciated that abolition must encompass racial equality as well as mere physical freedom from bondage. Members of the organization Witness to Innocence, which comprises exonerees from death row and gives them a voice in the anti-death penalty movement, have the potential to mirror the radical role that former and fugitive slaves played in abolition, by delivering their personal narratives and drawing attention to the cultural and institutional factors that lead to wrongful convictions in the first place. In 1845, James Henry Hammond wrote to James C Calhoun that “A Slave holder… or Southern man who falters, who apologizes, much less who denounces Slavery & regards abolition as inevitable is in my opinion our very worst enemy, the man who saps our strength at the core & does more to destroy us than a brigade of abolitionists could.” Drawing on this observation, we can see the vital role that Public Safety Officials on the Death Penalty might play. Formed in 2016, PSODP consists of current and former law enforcement personnel, prosecutors, and corrections officials who have concerns with capital punishment. Like former slaveholders, they can sap the strength of the pro-death penalty lobby in ways that brigades of other abolitionists cannot. Even the efforts to stem the supply of lethal injection drugs echoes the radicalism of the abolitionists who refused to be complicit in slavery. William Lloyd Garrison was particularly notorious for challenging Northerners to speak out against bondage, and to refuse to co-operate with the institution of slavery. The refusal of pharmaceutical companies and foreign governments to help with the administration of the death penalty has every bit of abolitionist potential as the refusal in the antebellum era to assist with the return of fugitive slaves.

Brandon Garrett has recently argued that the eventual abolition of the death penalty has the potential to instigate much needed changes to the criminal justice system more broadly, and while death penalty abolitionists will be celebrated for taking on a morally just but deeply unpopular cause, the legacy of the slavery abolitionists in contemporary efforts to make America a more just and humane place should not be overlooked.