“Mapping Memories of Enslavement”: The French Confront Their Own History

By Dr. Mattie Fitch

Like all European countries, France has a long history of participating in slavery, from slave labor in France’s colony of Saint Domingue that ultimately produced a massive slave revolt and the declaration of an independent Haiti, to forced labor in France’s African colonies that was modeled after the notorious system in the Belgian King Leopold’s Congo. The French revolutionary government of 1789 abolished slavery in France, but not in the colonies, where plantation owners practiced it widely. It was only after former slaves in Saint Domingue had already abolished slavery (and after radical Jacobins had taken control in Paris) that the National Convention outlawed it in the colonies in 1794, decreeing that “all men, without distinction of color, residing in the colonies, are French citizens and will enjoy all the rights assured by the constitution.”[1] When Napoleon came to power, he reinstated slavery in 1802. The revolutionary government of 1848 again abolished slavery, an event celebrated 150 years later in 1998 as the end of slavery in France and its territories. However, in the 19th and 20th centuries, the French brutally forced Africans to produce large amounts of rubber in colonies in equatorial Africa, resulting in a population loss of roughly 50 percent among the indigenous people (Adam Hochschild describes a similar murderous process in the case of Leopold’s Congo in his well-known book King Leopold’s Ghost).[2] This practice didn’t end until after the Second World War, and it wasn’t until 2001 that the French government recognized the slave trade and slavery as a “crime against humanity.” The resulting law (known as the Taubira law after Christiane Taubira, the politician who initiated it, a native of French Guiana, and a former Justice Minister who resigned in January 2016 to protest France’s anti-terrorism policies) established what is today the National Committee for the Memory and History of Slavery in order to assist the government with the “research, education, preservation, diffusion, or transmission of the history and memories of the slave trade, slavery, and their abolition.”[3]

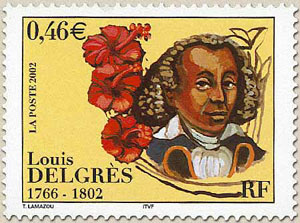

“Mapping Memories of Enslavement,” a project whose website has just launched, hopes to facilitate the analysis and commemoration of this history and its continuing effects. Largely the brainchild of scholar Dr. Nicola Frith, a Leadership Fellow with the UK’s Arts & Humanities Research Council and the primary researcher on the project, the website provides an interactive map of locations – “sites of memory” – and associated information relevant to the history and commemoration of slavery in France and its overseas territories. The “Memorial to the Sacrifice of Louis Delgrès and His Companions,” in Les Abymes, Guadeloupe, one such site, is the work of Guadeloupian sculptor Jacky Poulier and commemorates the armed fight in Guadeloupe against Napoleon’s troops and his attempt to reinstate slavery in 1802.[4] (An image of the sculpture can be found here.) The map also charts the network of contemporary activists, cultural associations, and government groups involved in bringing to light “France’s participation in the enslavement of peoples of African ancestry and the ways in which this history continues to negatively impact contemporary society.”[5] For example, on the map one can find information on the group “Blue roots routes de blues,” located on the Île de le Cité near the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, which aims to “promote musical exchanges among musicians of different cultures” and to “undertake work towards the remembrance of slavery.”[6] The “International Movement for Reparations,” another association represented on the map, in Fort-de-France, Martinique, was “the first organization to file a complaint against the French State calling for reparations for slavery” in 2005 after the passing of the Taubira law, and also works to “defend the memory of Africans who were deported then enslaved, as well as all peoples historically and currently who are victims of crimes against humanity and colonization, by putting in place procedures of reappropriation and preservation of their natural, historical, and cultural patrimony.”[7]

Frith and her research assistants, who make up the project team and could be considered activists themselves, aspire to strengthen the network of activists working to memorialize slavery or fight its contemporary repercussions. As scholars, they also endeavor to link organizers and academics by easing campaigners’ and researchers’ access to information useful to both. By fostering memorialization, their goal is to “contribute in a positive manner to the construction of memories of slavery in present-day France.”[8] In particular, the project interrogates the ways the French State has officially commemorated slavery and addressed its legacies, comparing these to grassroots efforts to bring attention to French complicity in the slave trade and recognize its victims, many led by activists from France’s overseas territories of Martinique, Guadeloupe, and La Réunion. Commemoration is only half of the story, however; by including contemporary activism in its purview, the project specifically aims to address questions of reparations and structural discrimination against the black community in France.

A Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of Edinburg, Frith draws upon her expertise in slavery studies and postcolonial studies. She has written a report, entitled “Memory, Slavery, Reparations,” which is based on interviews with activists and government figures and is available on the new website. The French website and report can be found here. The project team will continue to develop the map and add more sites of memory and organizations. An English-language version is also being prepared.

Follow “Memories of Enslavement” on twitter: @MemoriesSlavery

Dr. Mattie Fitch is an Assistant Professor at Tarleton State University. She studies modern French cultural and social history, particularly the Popular Front Movement and the interwar years.

[1] “Decree of the National Convention of February 4, 1794, Abolishing Slavery in All the Colonies,” The West and the World since 1500, The Bedford Series in History and Culture, eds. Lynn Hunt, David Blight, Bonnie Smith, Natalie Zemon Davis (Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2013), 393.

[2] Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost (Boston: Mariner Books, 1999).

[3] « Un Comité de personnalités qualifiées installé auprès du gouvernement par décret, » Le Comité National pour la Mémoire et l’Histoire de l’Esclavage, www.cnmhe.fr/spip.php?rubrique1 (5/25/2016).

[4] « Mémorial du Sacrifice de Louis Delgrès et ses compagnons – Les Abymes, » Cartographie des Mémoires de l’Esclavage, 2016 www.mmoe.llc.ed.ac.uk/fr/memoire/mémorial-du-sacrifice-de-louis-delgrès-et-ses-compagnons-les-abymes (5/25/2016) ; « En l’honneur de Louis Delgrès, » Comité National pour la Mémoire et l’Histoire de l’Esclavage, www.cnmhe.fr/spip.php?article687 (5/25/2016).

[5] “À propos de la CME,” Cartographie des Mémoires de l’Esclavage, 2016 www.mmoe.llc.ed.ac.uk/fr/à-propos-de-la-cme (5/25/2016).

[6] « Blue roots routes de blues, » Cartographie des Mémoires de l’Esclavage, 2016 www.mmoe.llc.ed.ac.uk/fr/association/blue-roots-routes de blues (5/25/2016).

[7] « Mouvement International pour les Réparations, » Cartographie des Mémoires de l’Esclavage, 2016 www.mmoe.llc.ed.ac.uk/fr/content/mouvement-international-pour-les-réparations (5/25/2016).

[8] “À propos de la CME,” Cartographie des Mémoires de l’Esclavage, 2016 www.mmoe.llc.ed.ac.uk/fr/à-propos-de-la-cme (5/25/2016).

One Comment, RSS