“African American History at Risk in Richmond”

By James Brewer Stewart, Macalester College

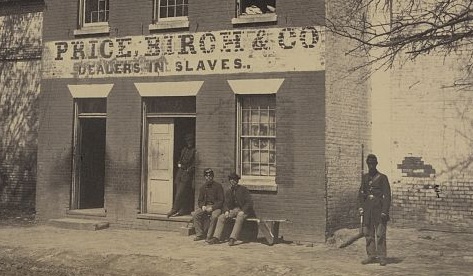

Throughout the antebellum decades slaveholders delivered tens of thousands of “their” enslaved people to Lumpkin’s Slave Jail (aka. the Devil’s Half-Acre) located in Richmond, Virginia. Lumpkin’s was only one of dozens of such enterprises scattered across the City where enslaved blacks were auctioned off and driven in chains into the Deep South. In all at least 300,000 African Americans passed through Richmond after falling prey to this vicious human trafficking, (aka. the interstate slave trade). A century and a half later, the Jail and its surrounding real estate it have become the focus of an intensive campaign by historians and activists to properly memorialize those victimized, to insure that the city honestly confronts its deep complicity in slavery, and to document the rich history of antebellum Richmond’s African American community. Richmond city officials, however, are entertaining far more modest plans.

Leading this campaign is the Defenders of Freedom, Justice and Equality, a prominent activist group which has consulted widely with community representatives and been guided by blue-ribbon consultants while developing a compelling and detailed plan for establishing a Memorial Park on the site: Sacred Ground Project. Their proposed project includes not only Lumpkin’s Slave Jail, but also nine surrounding acres that encompass the locale referred to as Shockoe Bottom, a community inhabited in antebellum times by poor and working class African Americans, Euro-Americans, Jews, Haitian immigrants, and Huguenot refuges. It is rich with long-buried African American sites and artifacts that surely deserve to see the light of day, not the least of which are a significant African-American burial ground and the site of gallows from which innumerable people were hanged, including those convicted of involvement in Gabriel’s slave rebellion of 1800.

The City is currently rejecting the Defender’ nine-acre proposal in favor of a project restricted to a modest commemoration to be located on the Lumpkin’s Jail site only. This is the nub of the controversy. Because the remains of the original Shockoe Bottom community are buried beneath fourteen feet of lawns, landscaping and also an asphalt parking lot, the City’s proposal leaves this history-rich real estate vulnerable to obliteration by jackhammers and bulldozers. Only a year ago, a site immediately adjacent to the Shockoe parcel was slated for transformation into a baseball stadium and shopping complex though that plan is currently off the table. Nevertheless, the Defenders of Freedom Equality and Justice worry that the City’s unwillingness to include the full nine acres is because the site’s potential to enrich the tax base trumps its historical significance. Were the City to construct the site as the Defenders have planned it, however, Richmond would be graced by a complex of exhibits, displays, reconstructions and memorials that would mark it as a distinguished example of how African American history can and should be presented.

For these compelling reasons, the Defenders blueprint for developing the Shockoe site has been endorsed by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and has attracted strong support from, among others, Preservation Virginia, the Richmond Branch of the NAACP, the Richmond Crusade for Voters, and by Historians Against Slavery, an international alliance of distinguished scholars and leading activists that promotes opposition to slavery today and to the racist legacies from slavery in the past. And, no doubt about it, the Defenders’ version of the future Shockoe site would be an immediate game-changer. No southern city devotes greater public space to dramatizing the heroic statures of illustrious slaveholders than does Richmond. In this respect, what the Defenders are insisting on by developing the nine acre Shockoe parcel is an equal playing field for African Americans when it comes to historic sites. The need is compelling and obvious. To illustrate:

The grassy boulevard of Monument Avenue, the city’s most impressive expression of turn of the 20th century opulence, features enormous equestrian statues of Robert E. Lee (67 feet in height), Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis, and J.E.B Stuart. The effect upon first encountering them can be akin to a slap in the face. In the late 1890s and early 1900s, Virginia’s Daughters of the Confederacy, led by members of the state’s most prominent white families, bankrolled the construction of these colossal evocations of slavery’s preeminent defenders as part of their ambitious programs to memorialize the “Lost Cause.” At just that same time, as these politically connected “southern ladies” keenly appreciated, Virginia’s State Government was busily promulgating harsh new regimes of racial segregation and black exploitation, a bitter historical narrative with which Richmond’s African American citizens are surely all too familiar. How many white citizens, one wonders, or, perhaps better, how few, embrace this African American understanding of history when gazing upon these statues? How many instead respond to the nostalgia of the “lost cause” that took up arms to defend slavery or simply think that “we’re past all that?” Contention percolates here.

Continue strolling and you encounter one more statue and contention multiplies. Furthest from downtown and facing away from it, well apart from its Confederate counterparts, is very much smaller statue of black local hero and universally admired tennis champion Arthur Ashe, designed by an acclaimed sculptor residing in Richmond and installed in 1996. Reflecting an undeniably post-Civil Rights sensibility, Ashe’s statute stands in dizzying contrast to the outsized Confederate equestrians. Ashe is presented as an AIDS-emaciated, life-sized figure, standing on his own two feet, holding a book and a tennis racket while the children clustered below, with faces alight, reach up to him. Disquieting questions arise. Is this a bitterly ironic dissent against the triumphal pretentiousness of the Confederate statuary? Might it offer a deeply tragic reflection of the overwhelming power of white supremacy? Might it represent Ashe’s and the children’s uncompromised humanity shining forth against the hubris and implicit racism of the Confederate statues? Might it register a spirit of racial submission that militants demanding equality might find offensive? Who can know? All that’s clear is that every possible meaning of Arthur Ashe’s statue amounts to a wholesale rejection of the Confederates as heroes, the monuments memorializing them and the history that they claim to represent.

These quarrelling historical representations inevitably provoke day-to-day antagonism, particularly in these tragically violent times. Last June, after the fatal shooting of nine African Americans at a church in Charleston, the Defenders of Freedom Justice and Equality petitioned in vain that the slaveholders’ statues be removed from Monument Avenue. Next someone spray painted the Jefferson Davis statue with “BLACK LIVES MATTER,” to which a neo-Confederate organization, the Virginia Flaggers responded by announcing a $1500.00 reward for information leading to the conviction of the perpetrator. Then, in early September, the Defenders of Freedom, Justice and Equality rallied at the foot of the Davis statue to protest its use as the half-way turning point in a world champion bicycle race put on by the Union Cycliste Internationale and heavily promoted by Richmond’s Mayor and business community. Said Ana Edwards, Chair of the Defenders’ Sacred Ground Historical Reclamation Project: “At a time when cities across the South are removing these symbols of oppression of black people, it is an embarrassment that our city, the former capitol of the Confederacy, would choose to highlight these statues to a world audience” A week later, the Virginia Flaggers responded as the protest continued by flying a plane overhead carrying a banner reading CONFEDERATE HEROS (sic) MATTER. The plane circled during the entire demonstration with the misspelled slogan. And so forth.

What’s made so painfully clear here is just how vitally important it is for Richmond to offer the public an historical site that breaks through the impasse, anger, and alienation generated by the statuary of Monument Avenue. This is precisely what the Defenders of Freedom, Justice and Equality’s Shockoe Bottom Memorial Park proposal of the Defenders of Freedom, Justice and Equality is designed to accomplish. Once constructed, citizens from all backgrounds and walks of life would be afforded rich opportunities to learn about City’s historical involvement with slavery, and to come to terms with it and with its implications, directly, honestly, and comprehensively. The historical record of a significant African American community would be presented in substance. Certainly, these are preferable outcomes to turning Shockoe Bottom’s nine acres into yet another high-end shopping center!

City officials have yet to formally reject the Defenders’ Memorial Park proposal. At this critical moment, widespread expressions of public support could well make all the difference. Please take a minute to review and endorse the Defenders’ proposal for the Memorial Park. Sacred Ground Project If you live in Richmond, contact your City Council Representative and Mayor. If you live in Virginia, contact your State Assembly Representative. And if you really want to pitch in, volunteer to spread the Defenders’ message DefendersFJE@hotmail.com and lend financial support to their cause: Defenders for Freedom, Justice & Equality.

Dr. James Brewer Stewart is the James Wallace Professor Emeritus at Macalester College, founder of Historians Against Slavery, and leading authority on American history. His book on abolitionism, Holy Warriors: The Abolitionists and American Slavery, is considered the best in the field.