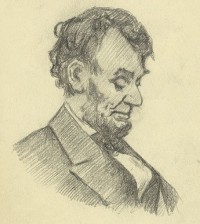

Lincoln, the 13th Amendment, and the “Cure for All the Evils”

By Dr. Christian Samito

In his first public address after Congress passed a resolution proposing to the states a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery nationwide, President Abraham Lincoln called the measure “a King’s cure for all the evils.” For more than ten years, Lincoln had used medical analogies in speeches and debates when referring to slavery, likening it to a “wen or a cancer” that could not be cut out easily lest the patient “bleed to death.” War had changed circumstances, however, so that on February 1, 1865, Lincoln now could identify a cure.

Lincoln also took the opportunity to make a pun with a deeper meaning. Doctors at the time prescribed evening primrose oil, also commonly called King’s cure-all, to remedy a variety of ailments. Lincoln had used the phrase “king-cure-all” once before, sarcastically, during an 1839 speech about the Democratic Party’s plan for where to secure the nation’s revenue. Lincoln now used the reference to acknowledge the complex and multifaceted nature of emancipation and to offer an optimistic opinion that the amendment would remedy the diverse problems caused by slavery.

***

Despite its simple wording, the Thirteenth Amendment profoundly changed the Constitution and the way Americans think about it. On one level, the amendment performed some obvious tasks: it abolished slavery and made the Constitution an explicitly antislavery document; it rendered moot the Fugitive Slave and Three-Fifths Clauses; and it eliminated the concept, outlined by Roger Taney in his Dred Scott ruling, that the Fifth Amendment protected property in human beings. Lincoln before the war had called for Taney’s Dred Scott ruling to be overruled, and, along with the amendment that followed it, the Thirteenth Amendment did just that.

In the process, the Thirteenth Amendment helped unite the American people in a stronger nation-state. For Lincoln, the Union was “perpetual,” yet slavery threatened his nationalistic vision. When Lincoln spoke of maintaining the Union, by necessity he would have required the destruction of the one institution that almost tore it apart. Moreover, with the Thirteenth Amendment, Lincoln envisioned a country unified in free labor economics and the ideals of the Declaration of Independence at the core of its nationalism.

***

The Supreme Court has helped shape the boundaries of the Thirteenth Amendment’s applicability. In the Civil Rights Cases (1883), the Supreme Court held that the Thirteenth Amendment established “universal civil and political freedom throughout the United States,” that its enforcement provision “clothes Congress with power to pass all laws necessary and proper for abolishing all badges and incidents of slavery in the United States,” and that it applies to private individuals and state acts. The Fourteenth Amendment, by contrast, applies only to state action. On the other hand, the Court also determined that the Thirteenth Amendment applies only to civil and political, not to social, rights and declared that segregation from public accommodations was not a badge or vestige of slavery. Justice John Marshall Harlan, the lone dissenter in this case as he would be in Plessy v. Ferguson, argued for a broader reading of the Thirteenth Amendment.

In the context of the post–World War II civil rights movement, the Supreme Court broadened the Thirteenth Amendment’s applicability. In Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Company (1968), the Court held that the amendment authorized Congress to eliminate private housing discrimination and “all racial barriers to the acquisition of real and personal property.” The Court also set out a deferential standard of review in considering legislation passed under the Thirteenth Amendment: “Surely Congress has the power under the Thirteenth Amendment rationally to determine what are the badges and the incidents of slavery, and the authority to translate that determination into effective legislation.” Holding that “when racial discrimination herds men into ghettos and makes their ability to buy property turn on the color of their skin, then it too is a relic of slavery,” the Court added, “The freedom that Congress is empowered to secure under the Thirteenth Amendment includes the freedom to buy whatever a white man can buy, the right to live wherever a white man can live. If Congress cannot say that being a free man means at least this much, then the Thirteenth Amendment made a promise the Nation cannot keep.” Jones prohibited racial discrimination in the making and enforcement of contracts, including as to the sale or rental of property, followed by Runyon v. McCrary (1976), in which the Supreme Court applied this concept to private schools to hold that they could not discriminate on the basis of race.

Today, legal commentators continue to debate the parameters of the second section of the Thirteenth Amendment. On one hand, this provision could be read to create a very broad congressional power to address human rights issues. On the other hand, the doctrines of federalism and the separation of powers still apply. Lawmakers knew about McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), and the role it preserved for judicial review, when they drafted the Thirteenth Amendment. The Jones court quoted from McCulloch. Not only does Congress’s power to legislate under Section 2 of the amendment have limits, but the courts play an important role in helping to define the law under the Thirteenth Amendment.

Recent law review articles argue for applying the Thirteenth Amendment across a range of issues, including race-based hate speech, racial profiling, race-based peremptory jury challenges, conditions in black communities, race disparities in capital punishment and health care, reproductive freedom, sexual discrimination and harassment, and discrimination of homosexuals. Since 2010 the White House has proclaimed January National Slavery and Human Trafficking Prevention Month, but extends it to culminate on National Freedom Day on February 1 (so designated because Lincoln signed on that day the resolution sending the Thirteenth Amendment to the states for ratification even though constitutionally he did not need to do so) to bring attention to an issue to which the Thirteenth Amendment undoubtedly applies.

Some law professors have called on Congress to use the Thirteenth Amendment to address labor issues beyond those with direct parallels with slavery, arguing that it contains broader language to deal with such concerns than does the Commerce Clause, on which Congress typically relies to do so. Before the New Deal, labor activists saw union rights to organize, boycott, and strike as coming from the First and Thirteenth Amendments, but legal professionals, wary of broad rights arguments, increasingly adopted the Commerce Clause as the preferred avenue to enact labor-related legislation. Law professor Alexander Tsesis further identifies the Thirteenth Amendment as the constitutional provision best suited to deal with civil rights and individual liberties. Tsesis notes that the Fourteenth Amendment addresses only state-sponsored matters, not private ones, and where an overriding public interest can permit the state to infringe on rights otherwise protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, even a compelling state interest does not justify a state or private infringement under the Thirteenth Amendment. Moreover, Tsesis observes, the Commerce Clause, though “grafted ingeniously into the civil rights arena,” needs an economic component to make it apply, whereas the Thirteenth Amendment does not.

On the other hand, some scholars warn against overextending the amendment’s applicability, wherein people try to apply it to matters they find undesirable but that are unrelated to slavery or involuntary servitude. Even under the deferential standard of judicial review articulated by the Supreme Court in its McCulloch ruling, means must be “appropriate” within the Thirteenth Amendment to be held constitutional pursuant to it. Furthermore, in its ruling in City of Boerne v. Flores (1997), which addressed the Fourteenth Amendment’s enforcement provision, the Supreme Court sent a message that it intends to continue patrolling the boundaries of congressional authority. While different lines of case law apply to interpreting the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, one can assume from its City of Boerne ruling that the Supreme Court would give broad deference to Congress in legislating pursuant to the Thirteenth Amendment but would strike down more radical theories about its applicability to issues unrelated to slavery or involuntary servitude.

Thus, the Thirteenth Amendment works as Lincoln likely hoped it would. As the “King’s cure for all the evils” wrought by slavery, Lincoln understood how the amendment could operate broadly to address various issues surrounding freedom and its definition. At the same time, the Thirteenth Amendment preserved the constitutional equilibrium: the president’s powerful voice can encourage certain readings of it, Congress can articulate the will of the people through legislation enacted pursuant to its second section, and the presidential veto and the Supreme Court can ensure that such legislation is appropriate to its enforcement. If the people disagree with the actions of any branch, they can turn to elections or the amendment process for corrective action. The Thirteenth Amendment accomplished Lincoln’s goal of bringing the Founding charter closer to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence while preserving its fundamental structure. For someone like Lincoln, who so greatly valued both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, there could be no more fitting monument to his legacy.

Christian G. Samito practices law in Boston and teaches legal and constitutional history at Boston University School of Law. His most recent book is Lincoln and the Thirteenth Amendment (Southern Illinois University Press, 2015), from which the above post was excerpted with permission. He holds a JD from Harvard Law School and a PhD in American history from Boston College and can be reached at Christian@christiansamito.com.

4 Comments, RSS